Scientists have identified four more ghostly signals of massive collisions in outer space, including of the largest to date, bringing their total haul of gravitational-wave detections to 11 in just a few years. And even better, that wealth of observations is large enough to let scientists make broader discoveries about the world around us and the black holes that fill it.

A team of researchers affiliated with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the U.S. and its European counterpart Virgo unveiled the four new detections on Saturday, December 1 at a scientific meeting.

“It took science a century to confirm Einstein’s prediction of the existence of gravitational waves,” Sheila Rowan, a physicist at the University of Glasgow in the United Kingdom, said in an interview. “But the pace of our discoveries since then has been exhilarating, and we’re anticipating many more exciting detections to come.”

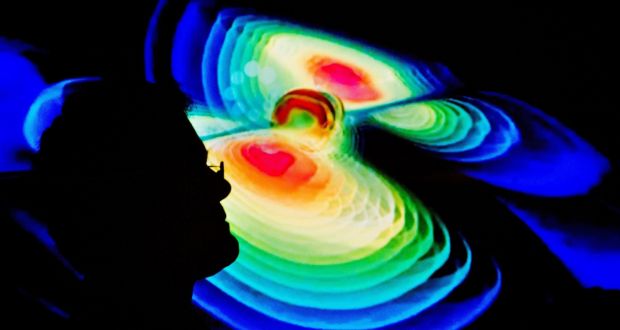

Gravitational waves are often described as “ripples in space-time” and are produced by pairs of black holes or neutron stars which are two forms of extremely massive, dense remnants created when a star explodes. Pairs of these objects orbit each other, drawing ever closer to one another and causing gravitational waves to ripple outward as they do so until they eventually collide.

Thanks to the LIGO and Virgo detectors, scientists on Earth can now capture these signals, which lets them study the collisions and objects involved. As the field of gravitational-wave science has matured, new detections have taken on a different tone. The first detection, which was announced in February of 2016, was remarkable for its very existence, but in the nearly three intervening years, binary black hole mergers have begun to verge on the routine.

The new announcement is the largest batch of detections released at once, and it includes an event that is both the most massive and the most distant collision observed to date. And now that scientists have a total of 10 binary black hole merger detections under their belts and one binary neutron star merger, announced last fall, they can start to draw some conclusions about black holes in general.

“Gravitational waves give us unprecedented insight into the population and properties of black holes,” Chris Pankow, an astrophysicist at Northwestern University, said in an interview. “for example, that most black holes formed by stars encompass less than 45 suns’ worth of material. We now have a sharper picture of both how frequently stellar mass binary black holes merge and what their masses are. These measurements will further enable us to understand how the most massive stars of our Universe are born, live and die.”

The newly announced gravitational-wave observations weren’t found in new data, in fact, both LIGO and Virgo have been down for upgrades since August 2017.

Instead, the new detections were found on another look through data gathered during the observing run that took place between Nov. 30 and Aug. 25, 2017. Scientists had already published three black hole mergers observed during that time frame, as well as the sole binary neutron star collision discovered to date.

The detectors are scheduled to begin observing again in early 2019 and scientists think they’ll spot two black hole mergers every month during that observing run. But in the meantime, they can keep poring over the four new discoveries.