Researchers from RIKEN and JAXA have used observations from the ALMA radio observatory located in northern Chile and managed by an international consortium including the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) to measure, for the first time, the strength of magnetic fields near two supermassive black holes at the centers of an important type of active galaxies. Surprisingly, the strengths of the magnetic fields do not appear sufficient to power the “coronae,” clouds of superheated plasma that are observed around the black holes at the centres of those galaxies.

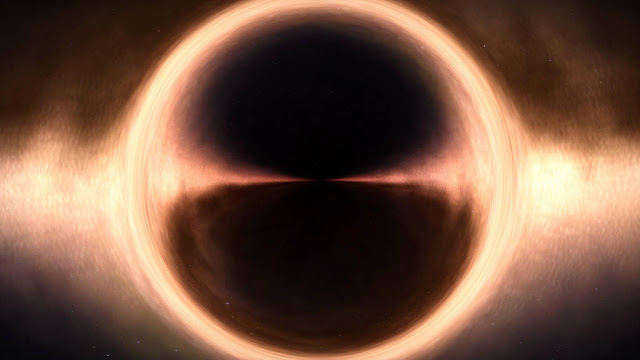

It has long been known that the supermassive black holes that lie at the centres of galaxies, sometimes outshining their host galaxies, have coronae of superheated plasma around them, similar to the corona around the Sun. For black holes, these coronae can be heated to a phenomenal temperature of one billion degrees Celsius. It was long assumed that, like that of the Sun, the coronae were heated by magnetic field energies. However, these magnetic fields had never been measured around black holes, leaving uncertainty regarding the exact mechanism.

In a 2014 paper, the research group predicted that electrons in the plasma surrounding the black holes would emit a special kind of light, known as synchrotron radiation, as they exist together with the magnetic forces in the coronae. Specifically, this radiation would be in the radio band, meaning electromagnetic waves with a long wavelength and low frequency. And the group set out to measure these fields.

They decided to look at data from two “nearby,” in astronomical terms, active galactic nuclei: IC 4329A, which is about 200 million light-years away and NGC 985, which is approximately 580 million light-years away. They began by taking measurements using the ALMA observatory in Chile and then compared them to observations from two other radio telescopes: the VLA observatory in the United States and the ATCA observatory in Australia, which measure slightly different frequency bands. The team found that indeed there was an excess of radio emission originating from synchrotron radiation, in addition to emissions from the “jets” cast out by the black holes.

Through the observations, the team deduced that the coronae had a size of about 40 Schwarzschild radii, the radius of a black hole from which not even light can escape, and a strength of about 10 gausses, a figure that is a bit more than the magnetic field at the surface of the Earth but quite a bit less than that given out by a typical refrigerator magnet.

“The surprise,” says Yoshiyuki Inoue, the lead author of the paper, published in the Astrophysical Journal, “is that although we confirmed the emission of radio synchrotron radiation from the corona in both objects, it turns out that the magnetic field we measured is much too weak to be able to drive the intense heating of the coronae around these black holes.” He also notes that the same phenomenon was observed in both galaxies, implying that it could be a general phenomenon.

Looking to the future, Inoue says that the group plans to look for signs of powerful gamma rays that should accompany the radio emissions, to further understand what is happening in the environment near supermassive black holes.