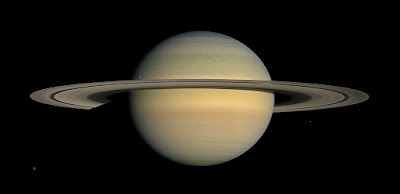

The building blocks of life are literally raining down on Saturn’s atmosphere from its iconic rings. NASA’s dying Cassini spacecraft detected streams of organic molecules falling from the rings into the planet’s gassy outskirts, according to new research published in Science. The iconic planet’s “ring rain” is more like a ring downpour, and it’s coming down much harder than anyone thought.

While Saturn has no solid surface and is too big of a planet to host life as we know it, the findings still have implications for our understanding of Saturn’s atmospheric chemistry, said Kelly Miller of the Southwest Research Institute, who co-wrote the paper with lead author Hunter Waite of NASA and several other scientists.

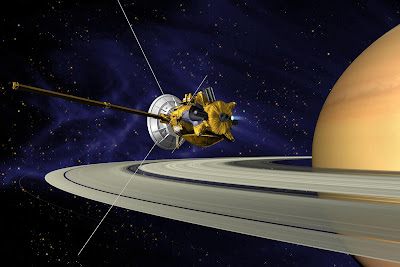

Scientists already knew that the rings delivered water to the atmosphere prior to these findings, but they didn’t realize how much. The new data — discovered when Cassini flew in between the rings and the planet for the first time in summer 2017 — shows that carbon- and oxygen-based molecules (specifically, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide) are also falling in.

“Water ice, along with the newly discovered organic compounds, is falling out of the rings way faster than anyone thought — as much as 10,000 kilograms of material per second,” Waite said in a statement. “The downpour coming from the rings included plenty of water as well as molecules like butane and propane — the kind of chemicals you might use for a grill or camping stove.”

Cassini’s ion neutral mass spectrometer and other instruments detected an infall rate of 10,000 kilograms (22,000 pounds) per second. That’s enough to completely deplete Saturn’s D ring in only 100,000 years, as long as the infall rate remains constant. The instrument also detected a high composition of carbon (more than 50 percent by mass) within the rings. This surprised scientists because they expected to see the lighter compounds of helium and hydrogen, which are both abundant elements in Saturn’s atmosphere.

“Saturn has a higher carbon/hydrogen ratio than Jupiter does, and the Cassini data indicate that if the current rate of inflow were sustained for millions of years, then the ring material could fully account for that enhancement,” Miller told. “If the inflow rate is variable, the inflow may still significantly contribute to the enhancement, depending on its time-averaged rate.”

>

“These high inflow rates strongly suggest that the innermost ringlets are being fed material by rings that are farther out,” Miller explained. “They also indicate the presence of material in the innermost rings which are too small to see with remote sensing techniques.”

Though the Cassini mission ended last year just weeks after it detected the ring downpour, the data it collected around Saturn between 2004 and 2017 will remain available indefinitely for scientific analysis. Miller didn’t say directly if she plans to plumb the old data for more examinations of the rings, but she has a few ideas in mind for future research.

Specifically, the scientific community still argues over the age of Saturn’s rings. Some researchers have suggested that they are as old as Saturn itself (4.5 billion years), while others studying Cassini data say that most of the rings formed while dinosaurs roamed the Earth during the Jurassic period roughly 200 million years ago. Miller indicated that with new information about the rate of change within the rings, scientists may eventually be able to pin down their age.

“These Cassini data reveal the presence of abundant nano-sized material coming from the rings, which can’t be observed remotely. They also allow us to directly measure the composition of the rings,” Miller said. “Together, this information changes what we know about the evolution and make-up of the rings. My hope is that these new puzzle pieces will help us constrain when and how the rings formed, which is something that I think a lot of people are curious about.”